One benefit of attending a liberal arts college is that you’re exposed to common themes in famous literature across the centuries and across cultures. We’re all familiar with these themes common to the human condition. Good vs. evil, love, or coming-of-age are just a few examples.

In the financial world, a common recurring theme is the so-called “death” of equities. The most famous example was the 1979 cover of Business Week boldly proclaiming the “Death of Equities.” A more recent example was the missive titled “Cult Figures,” written by a former “Bond King.”

Any author/investor who claims that equities are a dying asset class is brazenly using fear to manipulate your behavior. Business Week was simply trying to sell more copies to drive higher advertising revenue and the “Bond King” was simply pushing his fixed-income mandate.

In the remainder of this post, I’m going to share with you one allegory as the only antidote to fear – that of faith. However, the faith I’m describing is not based on blind belief, but soundly based in history.

A Story About a Former Bond King

Once upon a time, a Bond King ruled over the fixed-income world from a beach in Southern California. In 2012, at the height of his power, he proclaimed from his throne:

“The cult of equity is dying….Like a once bright green aspen turning to subtle shades of yellow then red in the Colorado fall, investors’ impressions of ‘stocks for the long run’ or any run have mellowed as well.”

The Bond King wanted to question the superiority of stocks as long-term investments. Although the de facto leader of the cult of equities is a well-known Oracle in Omaha, the Bond King didn’t dare try a direct attack. Rather than attack the unassailable track record of the oracle, the Bond King chose a different route.

Instead, he went about questioning the findings of the so-called “Wizard of Wharton,” author of the 1994 long-term equity investing bible, Stocks for the Long Run. After crunching two centuries worth of date, the “Wizard” found that equities had produced an annualized real return of 6.6%. This number famously came to be known as the “Siegel Constant.”

At the time, the Bond King wrote:

“Yet the 6.6% real return belied a commonsensical flaw, much like that of a chain letter or yes – a Ponzi scheme. If wealth or real GDP was only being created at an annual rate of 3.5% over the same period of time, then somehow stockholders must be skimming 3% off the top every year. If an economy’s GDP could only provide 3.5% more goods and services per year, then how could one segment (stockholders) so consistently profit at the expense of the other segments (lenders, laborers, and government)?”

The Most Important Chart in Global Finance

Shortly, I will explain shortly how long-term equity returns can outstrip economic growth without resorting to the belief in a global Ponzi scheme on behalf of equity investors. In the Bond King’s defense, I might also resort to sleight-of-hand explanations to explain away the superiority of equity returns if I were a fixed income manager.

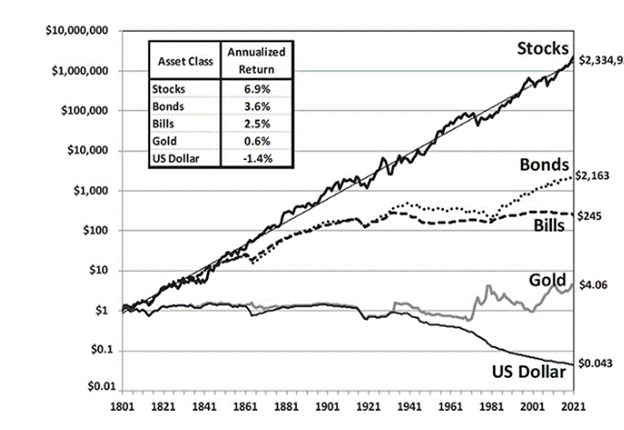

First, I present to you below the most important chart in the finance world. The data represents the most comprehensive collection of asset class returns that have been studied to date. The chart is taken from the 6th edition of Stocks for the Long Run and reflects 220 years’ worth of data (1802-2021).

The chart shows that the average real return on a broadly diversified portfolio of stocks has averaged 6.9% per year. This is slightly higher than the return data listed in the first edition of the book. The Bond King (who was subsequently deposed from his throne) felt that the 6.6% average annual real return from equities “is an historical freak, a mutation likely never to be seen again as far as we mortals are concerned.”

Equities for the Long Run

The chart above is based on a logarithmic scale. Therefore the straight line represents a constant percentage change and you can clearly see that the real return from stocks hugs the trendline. This is the closest to a constant that you’re going to find in the world of investing.

Once again, stocks produced the highest return of any asset class despite the inclusion of the dot-com bubble, subprime mortgage crisis, and Covid-related crash in Siegel’s data. Stocks produced a real return of 6.9% – a slight increase over the 6.6% obtained with his original data set.

Interestingly, if Siegel included the stock return data from the first half of 2022, then the real return is reduced to 6.7%. This value is roughly equivalent to the return data he first discovered over 30 years ago when publishing the first edition of his book.

Where Are All the Billionaires

Assuming you accept Siegel’s Constant, naturally the following question arises: Since stock returns compound much faster than GDP growth, why don’t stock investors end up owning the entire economy?

Siegel goes on to state:

“It would take only a mere $1 million invested in the stock market in 1802 to grow, with dividends reinvested, to $54 trillion at the end of 2021 – more than the total value of US stocks at this time.”

Total return data is calculated with the assumption that all dividends are reinvested. However, the reality is that it’s rare for either an individual or an entity such as an endowment or pension plan to accumulate wealth indefinitely without spending it. Even those who pass on fortunes to their heirs will find that the money is eventually spent by the next generation.

As Siegel states:

“Even those who bequeath fortunes untouched during their lifetimes must realize that these accumulations are often dissipated in the next generation or spent by the foundations to which the money is bequeathed.”

Human Nature Is a Failed Investor

John Neff of Akre Capital Management has an alternate theory and believes that investors make errors in judgment that end up short circuiting the compounding process. According to Neff, investors overreact to macro events and attempt to get out of the market before the next recession and then get back in before the recovery.

This sort of timing is impossible to achieve. Not only do you have to get the timing of the recession correct but also the market’s reaction. Ultimately, only a buy-and-hold approach can guarantee that you obtain the market’s total average return.

Conclusion

In my view, Neff’s explanation is more accurate. Investors are their own worst enemies and very few will ever realize the power of compounding returns that only equities can provide as an asset class.

Once again Siegel provides the following insight:

“In short, our inherent psychology militates against the buy-and-hold investor. As events shake the world markets, the strategy of “doing nothing” seems counterintuitive, if not downright irresponsible. Yet data have shown that attempting to “time” the market is a fool’s errand, and the buy-and-hold approach is the best strategy.”

Despite all manner of political, economic and public health crises, the superior performance of stocks over the past two centuries should provide any investor with the faith that equities will continue to provide superior long-term returns.

Additionally, given the current levels of inflation, I want to emphasize that stocks are real assets and are an excellent way to hedge against inflation.

In future, it’s likely that you will again encounter headlines proclaiming that equities are dead as an asset class. When this happens, you’ll do well to remind yourself that all previous calls for impending doom were all in fact premature. As the Wizard of Wharton wrote: “Fear has a greater grasp on human action than does the impressive weight of historical evidence.”

You can confidently maintain your long-term faith in equities, knowing that over two hundred years of data support your decision.

It was mostly Asian dolls again, but with more variety (like some BBW dolls),えろ 人形 including Doll Castle’s latest abomination.